|

|

|

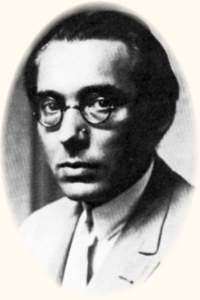

Lőrinc Szabó

|

Lőrinc Szabó (1900 - 1957)

An outstanding poet and translator of the second Nyugat generation, Szabó studied in Debrecen and Budapest and published his first book of poetry Earth, Forest, God [Föld, erdô, Isten] in 1922. He was heavily influenced by the German poet Stefan George (1868-1933) whose right hand in plaster form was kept by Szabó on his desk as a relic. After a revolutionary "Sturm und Drang" period of anarchistic revolt against the money- making ethics of society, Szabó made his 'Private truce' with reality, turning to philosophy and other less topical subjects. In 1944 he won the Baumgarten Prize, in 1954 he was given the Attila József Prize and in 1957 the Kossuth Prize.

Szabó's literary style shows a unique blend of intellectual perception and sensual experience. Few poets lived as passionately in the present as he did. Cricket Music [Tücsökzene], in which he told the story of his life in a brilliant sequence of poems, appeared shortly after World War II, in 1947. He devoted a major lyrical requiem to his dead lover in the volume entitled The Twenty-sixth Year [A huszonhatodik év], which appeared in 1957, shortly after his death and contained 120 sonnets. He developed the rhyming technique of the Hungarian language to an unprecedented degree; assonances and enjambments of a highly sophisticated nature became Szabó's personal trademark and signature.

PRIVATE TRUCE

If I had always known what I've learnt

over the years,

if I had always known that life was

squalor and tears,

I wouldn't be whistling now in the street,

walking so tall,

I would have surely hanged myself, to

finish it all.

With most other prodigal dreamers

I once believed

that the world and the human species

could be reprieved,

I thought that by force or by saying

a gentle word

many of us working together

could change the world.

Everything is much ghastlier than

I've thought before

but, thank God, I am not so squeamish,

not anymore,

I can face life's abominations

with open eyes,

that time and apathy succeeded

to immunize.

I've seen through all the old disguises,

those flimsy veils,

at thirty three I cannot be fooled

by fairy tales:

I see now, life is much nastier

than I had guessed

when as a young man I was about

to leave the nest,

I see the suckers being cheated

day after day,

poor sucker can't help being a sucker,

try as he may,

I see how reason becomes the whore

of interest,

how villains dress up as Galahads

on holy quest,

I see the noblest causes soiled by

the too-many,

I see that only death can bring us

true harmony, -

and since this isn't a fact to despise

or to deplore,

and since the seed of all human things

is bloody war:

I look at life, with calm resolve

and patience steeled,

as a doomed leper colony, or

a battlefield.

If I had learned about these perils

all at a blow,

I would have certainly hanged myself,

some time ago.

But fate must have planned a part, it seems,

for me to play:

it taught me everything, but slowly,

the gentle way:

this is why I signed a one-man truce,

a private one,

and this is why I do dutifully

what must be done,

this is why I think there are moments

worth living for,

this is why I am writing poems,

in time of war,

so I whistle among the lepers,

and smile inside,

and I am growing very fond of

the simple child.

|

|

|