Balázs Beöthy: Three Times Three Perspective, East of

Eden, (100cm x 433,5cm), 1999

vTBB: Peace and Progression:

Budapest Wunderground

Peace, peacepipe, and Indian. One of the key figures of the 1960s and 70s Budapest underground life proposed to do it the indian way (saying „let’s attend the indian school”). As we know, in the North American indian societies there were no schools (neither prisons, nor money, nor private ownership). By contrast, in East Central European countries, the training of artists was so academic that, till the mid-1980s there were few masters in these countries who were not self-taught or had not chosen to learn from each other.

In the photograph of Balázs Beöthy entitled This Song is About Nothing, is the artist himself, dressed as an Indian, dancing on the roof of a housing estate building, where he spent some of his childhood. Beöthy is not a photographer. He started his career as a member of the artist group called Hejettes Szomlyazók (Substitute Thirsters) in the 1980s. The primary interest of this group was action and installation. After the group split up in 1991, Beöthy kept working in the latter field. The works presented here were made when digital photography was over its boom, and the galleries were flooded by computer-prints.

Balázs Beöthy: Three Times Three Perspective, East of

Eden, (100cm x 433,5cm), 1999

The Three Times Three Perspectives, East of Eden with its philosophical humour presents the Garden of Eden of the judeo-christian mythology, in modern environment. Beöthy and his girlfriend are standing on the grass of a Budapest public park, staring at their navels. In Hungarian, navel-staring is a slang for hanging around. Of course, this pejorative and sarcastic phrase is the heritage of a 19th century culture that hasn’t known the concept of relaxation and meditation. Beöthy’s work of art refers to this change, and this is why he is not meditating, but obviously staring at his navel. Moreover, they’re doing it next to a notice to be found in almost all Budapest public parks, warning people to keep off the grass. Thus, in the context of the judeo-christian mythology, we can see the idyll just before the Fall, not only in today’s environment, but narrated in present terms. It is well known what came next: Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge, the Lord’s angel expelled them from the Garden of Eden, and they with all their offspring become mortal, sentenced not to take delight in the wonders of life anymore.

Róbert

Szabó-Benke was born in Yugoslavia, and he started his career there in

the late 1980s. In 1991 he escaped from the Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian War

to Budapest. Note that almost every decades of the history of this region

during the 20th century was so politicaly cataclismic that induced one

after another wave of emigration. The series entitled My Uncle’s House

portrays the home of a relative of the artist, who had previously lived

in France for quite a while. However, this fact doesn’t change anything

in the style and values with which he furnished his home. The idols of

the contemponary culture (Fanta can and Marlboro box, Mickey mouse, etc.)

fit easily into the conventional cushions, padded pheasants, and the typical

utility and fancy items of an ordinary East European home. This is an idyll

too, some kind of Eden, the summary of which, with all the experiences

of life behind, one considers beautiful. It is another story what the new

generations say of all this.

Róbert

Szabó-Benke was born in Yugoslavia, and he started his career there in

the late 1980s. In 1991 he escaped from the Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian War

to Budapest. Note that almost every decades of the history of this region

during the 20th century was so politicaly cataclismic that induced one

after another wave of emigration. The series entitled My Uncle’s House

portrays the home of a relative of the artist, who had previously lived

in France for quite a while. However, this fact doesn’t change anything

in the style and values with which he furnished his home. The idols of

the contemponary culture (Fanta can and Marlboro box, Mickey mouse, etc.)

fit easily into the conventional cushions, padded pheasants, and the typical

utility and fancy items of an ordinary East European home. This is an idyll

too, some kind of Eden, the summary of which, with all the experiences

of life behind, one considers beautiful. It is another story what the new

generations say of all this.

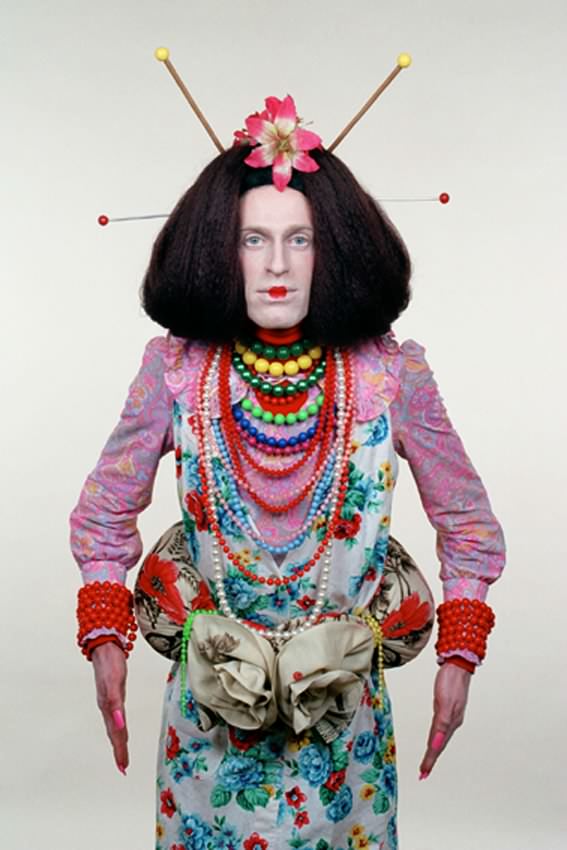

In Róbert Szabó Benke’s Konyi Baba series (where the artist depicts himself as a geisha) or in his My Beautiful World cycle (in which he dresses his models like a geisha and as an Indian), just as in Krisztián Kristóf’s Little Nemo series, the roles are fictional but the persons and sites are very real. The photograph Kitch'n Fashion presents the dress improvised of quilt, at an extempore alternative fashion show, but other images in the My Beautiful World series are also about fitting, i.e. fashion photos, but just formally. Still, one can explain the series as a playful, but not so happy self-concept of the young generation. In his series, Krisztián Kristóf together with Little Nemo are flown over today’s Budapest in their bed. The brands of the cars we see below make it unmistakeable. But how can this appear in century-old photos? Jorge Luis Borges can tell, whether it is his dream of us or we dream his dream.

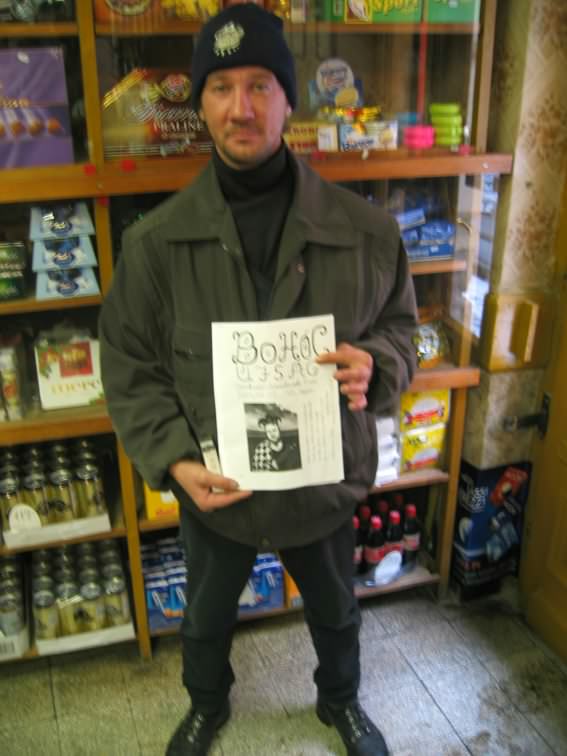

Krisztián

Kristóf is the youngest artist presented here; he grew up in the post-soviet

system. Kristóf graduated last year, then he moved to Finland. His

work of art Folklorid at first glance is a cartoon strip; in reality

it is the result of a project. Folklorid refers to the most serious

social problems of this area: increasing poverty and homelessness. In the

last fiteen years in the Eastern European countries witnessed a dramatic

stretching of the gap between the rich and the poor, which now outweighs

even the Western European average.

Krisztián

Kristóf is the youngest artist presented here; he grew up in the post-soviet

system. Kristóf graduated last year, then he moved to Finland. His

work of art Folklorid at first glance is a cartoon strip; in reality

it is the result of a project. Folklorid refers to the most serious

social problems of this area: increasing poverty and homelessness. In the

last fiteen years in the Eastern European countries witnessed a dramatic

stretching of the gap between the rich and the poor, which now outweighs

even the Western European average.

Krisztián Kristóf’s cartoon strip summarizes an average day of a homeless person nicknamed The Clown. The story was not invented by him; Kristóf followed his model for days, taking notes with his camera. His cartoon strip compresses several hundred photos into one page. The homeless person earns his living selling his own Xerox-copied newspaper. Krisztián Kristóf published this work in the very paper.

Another approach to the problem of homelessness is the 1997 project Inside Out by the Big Hope group. The two founders, the Scotsman Dominic Hislop and the Hungarian Miklós Erhardt, met at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts while studying there, and then they became art-mates. The basis of their cooperation is not only their social sensitivity and criticism of globalism, but their commitment to potential artistic strategies. This work of art presents the life of the homeless of Budapest. At the same time, the artists' method of facilitating rather then mediating communication, challenges the traditional ways of artistic - and social - representation and/or documentation, by questioning the hierarchy inherent in them.

Fra Angelico: The Last Judgement (detail: Hell) - Lenke

Szilágyi: Cinetrip 4 / New Era (2004, 2005)

As a new wave photographer, Lenke Szilágyi was interested in the 70/80s subcultures of Budapest. For the last quarter century, she could travel to remote areas. Her viewpoint enlarged rather than changed: the World – from Bronx to Irkutsk, from Helsinki to Delhi – does not really differ from her Budapest. In the pools of the old-fashioned public bath called Rudas, the young people having a party remind us of painters of Doomsday paintings from the 15th centrury. The trumpets of the Lord’s angels raise the spirit of the dead. Szilágyi’s new cycle entitled New Era mostly diverges from her earlier works in the respect that it is the first series she made using a digital camera.

Lódz Kaliska: Go for it / NEW POP, 2003

The Polish artist group Lódz Kaliska was also launched in the 80s. Their primary interests were actions, happenings, and performances which were improvised away from official exhibition institutions, at home parties, in private flats, and on excursions involving the audience. They documented some of their events with their own Super-8 films and photos, which eventually became their genre. Since the mid-80s there is no other city outside Poland where they are as well known and appreciated as in the art-scene of Budapest.

Lódz Kaliska’s newest cycle is entitled New Pop. Some parts of it, for example The Nation Is Still Going Strong (with the members of the group in the middle) or The Burning Chariot, are scenes from their newer movies (not longer than 2 minutes) or stagey, set photos. Since the end of 90s, Lodz Kaliska have been more conscious of presenting their socially critical and mostly provocative works not simply in an artistic context, but as ads of actual products and companies, advertised for the wider public that is not neccessarily motivated by the contemporary art.

Finally, I would like to frame all of our themes with the images of

the Danube (which is the biggest river in the area, but shapes the view

of Budapest more than anywhere else). The photo-sequences of Gabriella

Csoszó are partly comments, partly interludes for the other atrists’ works,

however the entire sequence can be interpreted even as a metaphor.